El Nino/La Nina Defined and Ski Areas Favored by El Nino (as of 2024)

|

The El

Nino/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) has been studied extensively for

its impacts upon climate. The shorthand definition of El Nino

is an abnormal warming of the normally cold ocean waters of the

Humboldt Current off the coast of Peru.

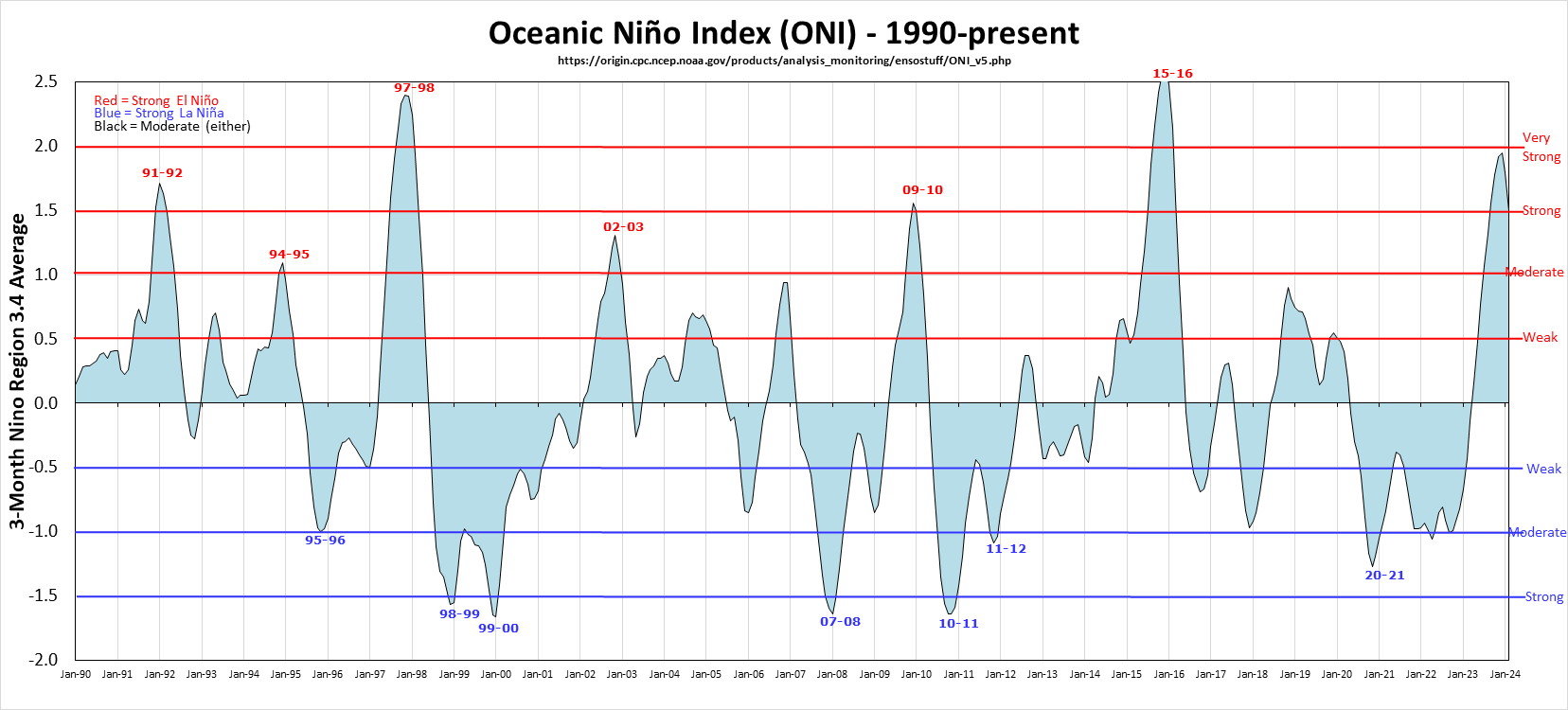

The Oceanic Nino

Index tracks equatorial sea temperatures

between 120 and 170 west longitudes, graphed below since 1990:

As most of us have observed, skilled weather forecasting has become very accurate in the short term, very useful for storm-chasing 3-5 days out, but more speculative beyond a week. Beyond 2 weeks I find it more useful to rely on historical records. El Nino/La Nina is the exception to this rule of thumb because the condition tends to persist for several months at a time. I have examined the monthly MEI table and the monthly ONI table , which both date to 1950. With over 800 monthly values since 1950, each month's indices can be correlated with the index 1, 2, 3, etc. months in the future to demonstrate how likely an El Nino or La Nina condition might persist. Results are shown here:

Notice that there is a very mild

tendency for El Nino/La Nina to reverse itself 14-30 months in the

future (think of a bathtub sloshing one side to the other), and

only after 3 years do all effects of prior conditions disappear.

This pattern and overall level of persistence is similar with both the MEI and ONI indicies.

When I first wrote this article on 11/21/07 the last posted value of MEI was

-1.117 for SEP/OCT 2007 (also -1.1 for ASO ONI), and I expressed strong confidence

that the observed La Nina condition would be in effect through the

end of 2007, and some confidence that it would persist for the

entire 2007-08 ski season. It turned out that La Nina remained strong (2007-08 was 5th

highest La Nina by MEI and 3rd highest by ONI in the past 50 years) through FEB/MAR, then

dissipated to near neutral by MAY/JUN for MEI and a couple months later for ONI.

Similarly the El Nino of 2009-10 was strong through FEB/MAR

(the 7th highest El Nino in the past 50 years by both indicies), but both turned negative

by June. By AUG/SEP 2010 MEI registered -1.88, the strongest La

Nina reading since 1974, and ONI reached -1.6 in October. The La Nina of 2010-11 remained

strong through April (the 3rd highest by MEI and 6th by ONI in the past 50 years) before weakening

in late spring. La Nina strengthened to a moderate level by

fall 2011 and gradually weakened the following spring. The MEI Index did

not have a sustained significant El Nino or La Nina stretch for the next 3 ski seasons.

From late spring 2015 to early spring 2016 El Nino exceeded +2.0 for 9 months by MEI and 6

months by ONI and was the highest overall by ONI and 3rd highest by MEI in the past 50 years.

The 2015-16 El Nino ended abruptly in June 2016. The northern spring months are the historically

most likely time for an El Nino or La Nina to break up, as occurred for all 7 events

from 2007-2024. There were no material El Nino or

La Nina deviations in the MEI or ONI indices from 2017-2020 aside from a mild La Nina in early 2018

and a borderline El Nino in early 2019, so I did not update the data presented here until after

the moderate La Nina of 2020-21. That La Nina persisted for 3 seasons into early 2023 but the two

indices diverged during 2022-23 when La Nina remained consistent by ONI while strengthening

by MEI. The La Nina dissipated by early spring for both but the ensuing 2023-24 El Nino topped out at

+2.0 by ONI but only +1.1 by MEI. The recent El Nino has weakened but as of MJJ 2024 the ONI is still +0.2,

though the MEI is now moderate La Nina at -0.7.

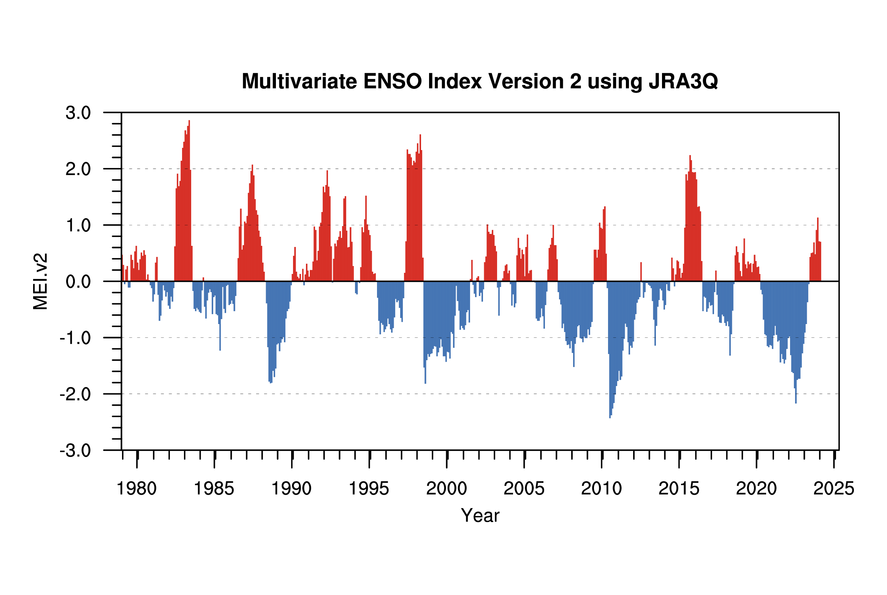

The original MEI index came to an end in

OCT/NOV 2018. The MEI graph at the top of this page is the new MEI.v2 from 1979 to JAN/FEB 2024.

The two MEI indices are calculated differently but are

95% correlated. MEI.v2 is used to compare snowfall for NOV/DEC 2018 and later months. In

recent years most meteorologists are using the ONI, so I'm doing that too as of 2023. Since 1950

monthly ONI is 88% correlated to monthly MEI and ski season values are 94% correlated. The

relationship of ski area snowfall to El Nino/La Nina is essentially the same for both MEI and ONI,

as illustrated in the short tables of El Nino favored areas below. With no material differences,

I show only one longer table on my Ski Areas Favored by

La Nina and Ski Areas

Indifferent to El Nino/La Nina webpages.

I had noticed anecdotally that the larger El Nino and La Nina episodes tend

to break up most often during the Northern spring. So tested by each calendar month

the correlations 1 month and 6 months into the future. The one month correlations

are all over 90% but they are highest between July and January. The 6 month

correlations are more revealing. An August or September reading of either MEI or ONI,

available in early September or October, has an 80+% correlation with what we'll have

during the middle of the upcoming Northern Hemisphere ski season. For South America

this has much less predictive value, as El Nino/La Nina during their ski season has

less than 20% correlation with its status 6 months prior. While we have

established that El Nino/La Nina are persistent weather events,

their effects upon ski area snowfall are less clear-cut. I

have correlated the monthly MEI table and the

monthly ONI table

with all of the monthly snowfall data I have collected through 2023,

and the list of ski areas with statistically significant snowfall

sensitivity to El Nino/La Nina is much shorter than most people

think. The monthly

correlations are not large enough to have much predictive value.

But by combining 6 consecutive months together to form seasonal

data, the correlations for some areas get into the 50% range. This

fits with observed experience that in big El Nino or La Nina years

the expected effects occur from time to time but not consistently.

So I considered the seasonal correlations to be the main criteria

in classifying areas. Not all areas provide complete November to

April data, and I like to have 20+ seasons to draw

conclusions. For areas

without enough complete seasons I looked at the monthly

correlations, but also at the seasonal ones for nearby areas with

many complete seasons. For example Sugar Bowl is likely to be

affected similarly to nearby Donner Summit and Alpine

Meadows. It is important to realize that season correlations

based upon 22-70 data points have much more uncertainty than the El

Nino/La Nina persistence correlations based upon over 700 data

points. Correlations are not

necessarily the best way to analyze El Nino/La Nina. Many meteorologists

believe that only the stronger episodes have a material impact. Thus we

should only examine snowfall during the months with the highest and lowest

MEI readings. I chose months above +.700 for El Nino and below -.700 for

La Nina. The problem here is that when I first collected this data in 2007

there had been only 3 La Nina seasons in the past 30 years, and only a few

areas had data from the La Ninas of the early and mid-1970's. Since the 2

strong La Ninas of 2007-08 and 2010-11 there is now more data, so I've revised

my tables to show snowfall percents of normal for strong El Nino months and

strong La Nina months. These columns are blank for areas with less than 22

months of data, which at a minimum would be all La Nina months December-March

from 1988-2021. The list of ski

areas favored by El Nino, along with their monthly and season

correlations to the MEI index and ONI index and average snowfall during strong

El Nino and La Nina months, is shown below:

El Nino

strongly favors only Southern California, Arizona and southern New Mexico,

with milder effects extending to the southern Sierra, far southern Utah

and northern New Mexico. In El Nino years the only big destination resort

that is favored is Taos, and that in the

mild category. Taos takes until nearly February to get

fully covered in normal years, and skiers should be more wary

during La Nina years. The Ski Apache data is derived from SNOTEL water

content but so extreme as to be worthy of inclusion. At its inland 33 degree

latitude there is normally more precipitation in summer than winter and La Nina

winters are almost guaranteed to be extremely dry.

The data I acquired for Las Lenas in

2005 and Portillo in 2007 support the prevailing view that the high

Andes are strongly favored by El Nino. As the 2010-11 La Nina strenghtened

these areas received almost no snow after August 1, 2010.

Advance bookings to these lower latitude South American ski areas

(also the Valle Nevado group) should be avoided in La Nina years

until snow is on the ground. I have

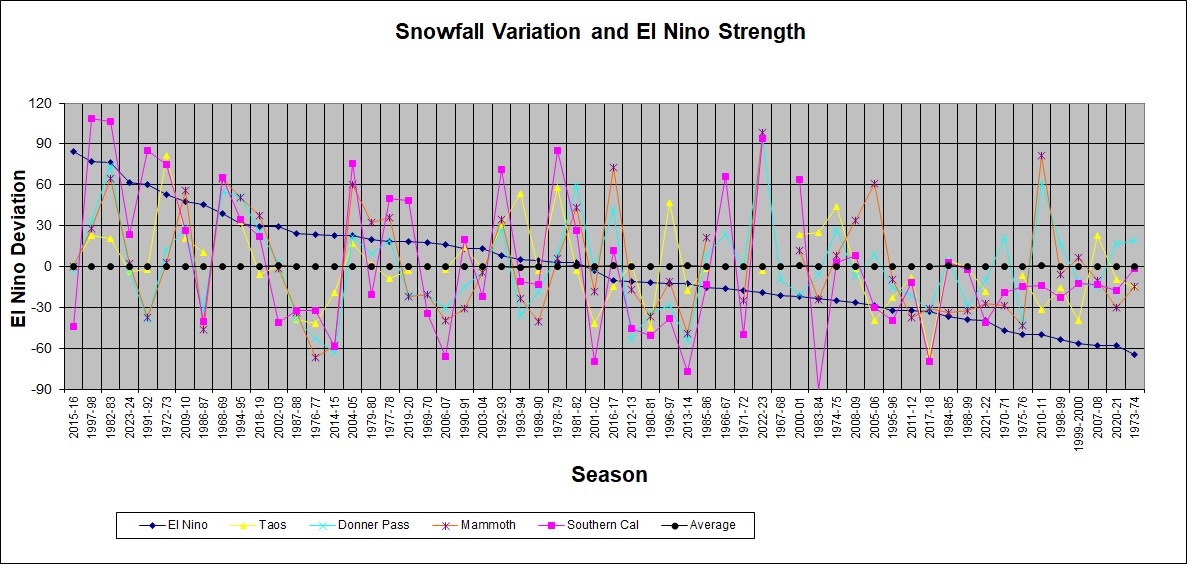

constructed graphs to illustrate the variability of the

snowfall correlations to El Nino/La Nina. The one below is

for selected areas favorable to El Nino. Since 2 of the

strongest La Nina years were 1973-74 and 1970-71, I select areas

with data that goes back that far. The horizontal

axis lists the ski seasons since 1966-67 in order of strong El Nino at

left to strong La Nina at right according to ONI. The vertical axis

is percent deviation from normal snowfall. The blue line is the sum

of ONI indices from OND to MAM, scaled to fit the

graph. The purple line

shows the dramatic boost to Southern California snowfall from El

Nino, with the 2 biggest snow years correponding to the 2 big El

Ninos of 1982-83 and 1997-98. 5 of the top 9 El Ninos produced

at least 170% of normal snow. There are no guarantees even

here, as the #1 and #5 seasons 2015-16 and 1986-87 were real stinkers at only

59% and 62%. Of the top 10 La Nina seasons only 2010-11 was above

average in Southern California, though only one was lower than 77%. Moving to Taos

(yellow line) the effect is less dramatic. The 1983 and 1986 El Ninos

were 116% and 118% of average, while Taos' record 1972-73

season at 174% was in the 5th highest El Nino year.

2023-24, 2015-16 and 1991-92 of the top 8 EL Nino years were below average at

Taos, but those were still at least 95% of average. For the top 9 La

Nina years, Taos is missing data for 1970-71 and 2007-08 was above average.

1999-2000 and 2010-11 were bad at 58% and 65%, and the other 4 were below

average in the 85% range. In the Sierra

the picture is mixed. Everyone remembers the huge Sierra

snow during the El Ninos of 1982-83 and 1997-98. But the 4rd and 5th

strongest El Ninos (1991-92 and 1986-87) were severe drought years

at Tahoe, and 1986-87 was Mammoth's 4th worst season ever at

55%. Nonetheless 7 of the top 13 El Nino years (1968-69, 1982-83,

1992-93, 1994-95, 1997-98, 2009-10 and 2018-19) were at least 130% at Mammoth (orange

line) and at Donner Summit (light blue line) and Lake Tahoe. At Donner Summit

3 of the top 4 La Ninas and 5 of the top 8 are above average. Lake Tahoe

La Nina seasons are probably assisted by colder temperatures

minimizing low elevation rain. This relatively good La Nina

track record is the reason that the MEI correlations are low and

statistically insignificant for areas like Kirkwood, Squaw Valley

and Alpine Meadows.

Historically Mammoth is classified with Taos in

mildly favored by El Nino category. Before 2010, 10 of the top 11 La Nina seasons

were all below average, 5 of them by 30% or more. However Mammoth set a

40+ year snowfall record during the strong La Nina of 2010-11, lowering its

seasonal correlation with MEI from 28.6% to 17.9%. Mammoth's near average snowfall

during the strong El Nino of 2015-16 further lowered seasonal correlation to 16.3%,

and finally another record high season during 2022-23 lowered the MEI correlation

to 13.9%. Bear Valley has a similar weak correlation to El Nino as Mammoth. As of 2023

Mammoth and Bear Valley average 98% and 96% of normal snow in MEI defined strong La Nina months,

which could move those two areas to neutral overall vs. El Nino/La Nina. For the time

being I've left these areas in the mild El Nino favored group due to the spread between

strong El Nino and La Nina months being 13-17% according to the ONI. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||